In Australia, 4.74 million people over the age of 50 have been classified as having osteoporosis, osteopenia or poor bone health (Osteoporosis Australia, 2023). Osteoporosis is characterised by low bone mass and the disruption of bone microarchitecture which compromised bone strength and can lead to an increase in the risk of fractures (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2023). The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines osteoporosis when bone mineral density is below -2.5 SD. Osteopenia is defined as a T-score between –1 and –2.5 SD (Osteoporosis Australia, 2023).

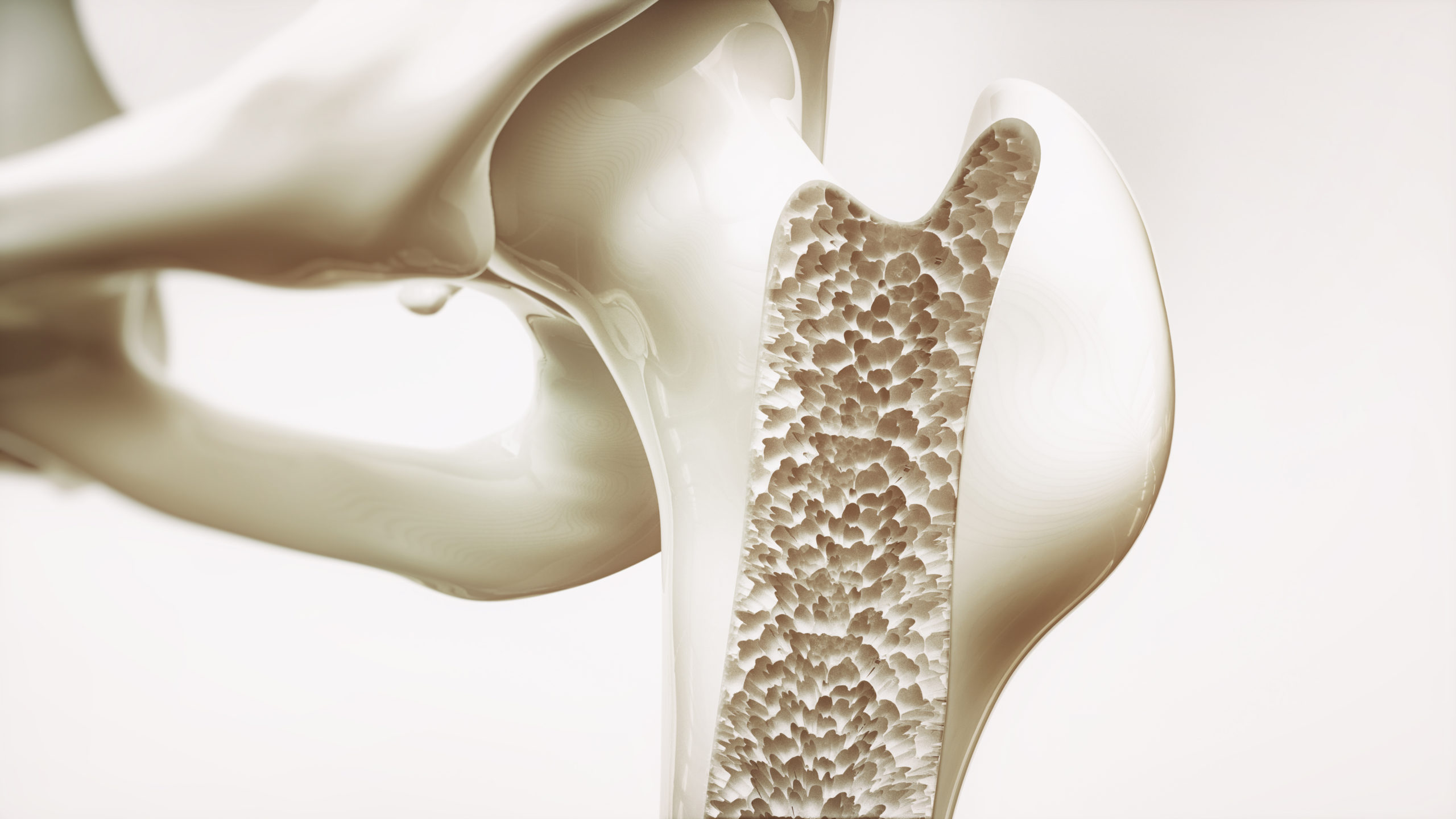

In the human body there are 206 bones made up of living tissue. The three types of bone tissue include:

- Compact – the harder outer tissue

- Cancellous – the sponge-like tissue

- Subchondral – the smooth tissue at the ends of bones, which is covered with another type of tissue called cartilage. Cartilage is a specialised, rubbery connective tissue.

(John Hopkins Medicine, 2021)

Understanding Bone Anatomy

To understand the role of exercise and physiotherapy in bone health, it is essential to understand the anatomy of bones. Bones are composed of living tissues that continuously undergo a process called remodelling – a process which involves the removal of old or damaged bone tissue (resorption) and the formation of new bone tissue (ossification) (Sözen, Özışık, Başaran, 2017).

- Bone Cells: Include osteoblasts (bone-forming cells), osteoclasts (bone-resorbing cells), and osteocytes (mature bone cells). These cells work to maintain bone health and integrity.

- Bone Matrix: The matrix of bone tissue consists of collagen fibres and minerals such as calcium and phosphate. Collagen provides strength and flexibility, while minerals contribute to bone hardness and density.

- Bone Structure: Bones have a hierarchical structure, starting from the microscopic level with collagen fibres and mineral crystals, to osteons (structural units) at the macroscopic level, forming compact and spongy bone regions.

- Bone Marrow: Inside certain bones, there’s bone marrow, which produces blood cells (red marrow) and stores fat (yellow marrow). Bone marrow is crucial for haematopoiesis (blood cell formation) and immune function.

(Sözen, Özışık, Başaran, 2017)

The Impact of Exercise on Bone Structure

Regular exercise, particularly weight-bearing and resistance activities, exerts beneficial effects on bone health (The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners., 2017). Here’s how exercise influences bone structure:

- Bone Density: Weight-bearing exercises like walking, running, and jumping stimulate osteoblast activity, leading to increased bone density and strength.

- Bone Remodelling: Exercise induces mechanical stress on bones, triggering the remodelling process. This involves osteoclasts breaking down old bone and osteoblasts forming new bone, resulting in improved bone quality.

- Muscle-Bone Interaction: Strong muscles exert forces on bones during exercise, promoting bone adaptation and remodelling. This muscle-bone interaction is crucial for overall skeletal health and functionality.

- Joint Support: Exercise enhances joint stability and mobility, reducing the risk of joint-related injuries and preserving bone integrity around joints.

The Role of Physiotherapy in Bone Health

Physiotherapy complements exercise by focusing on specific techniques to optimise bone health and function. Here’s how physiotherapy impacts bone structure:

- Muscle Strengthening: Physiotherapy programs include targeted exercises to strengthen muscles around bones, providing better support and reducing the risk of fractures.

- Balance and Coordination: Physiotherapy improves balance and coordination, essential for fall prevention and maintaining bone health, especially in older adults.

- Pain Management: Physiotherapy techniques such as manual therapy and therapeutic exercises alleviate pain associated with bone and joint conditions, enhancing mobility and quality of life.

- Joint Mobility: Certain physiotherapy techniques aim to improve joint mobility and flexibility. This is beneficial for overall movement and function, preventing stiffness and reducing the risk of joint-related injuries.

Exercise and physiotherapy are powerful tools for maintaining strong and healthy bones. By understanding bone anatomy and incorporating targeted physical activities and therapeutic interventions, you can minimise or even reverse the effects of osteoporosis. Feel free to contact us for more personalised guidance and support on your journey to optimal bone health.

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2023, December). Osteoporosis and minimal trauma fractures. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/chronic-musculoskeletal-conditions/osteoporosis

John Hopkins Medicine. (2021, May 3). Anatomy of the bone. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/anatomy-of-the-bone

Osteoporosis Australia. (2023). Osteoporosis costing all Australians A new burden of disease analysis – 2012 to 2022. https://healthybonesaustralia.org.au/

Sözen T, Özışık L, Başaran NÇ. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017 Mar;4(1):46-56. doi: 10.5152/eurjrheum.2016.048

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. (2017). Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis and management post-menopausal women and men over 50 years of age. 2nd Edn. https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/osteoporosis/executive-summary